Several tales under the British Library’s Magna Carta room, alongside a rumbling line of the London Underground, is a brightly lit labyrinth of uncommon and historic objects. Previous a collection of vintage rifles chained to a wall, previous an intricate system of conveyor belts whisking books to the floor, the library shops an unlimited assortment of performs, manuscripts, and letters. Final spring, I checked my belongings at safety and descended to sift by this archive—a file of correspondence between the producers and administrators of British theater and a small group of censors who as soon as labored for the Crown.

For hundreds of years, these strict, dyspeptic, and generally unintentionally hilarious bureaucrats learn and handed judgment on each public theatrical manufacturing in Britain, putting out references to intercourse, God, and politics, and forcing playwrights to, as one put it, prepare dinner their “conceptions to the style of authority.” They reported to the Lord Chamberlain’s Workplace, which in 1737 grew to become liable for granting licenses to theaters and approving the texts of performs. “Examiners” made certain that no productions would offend the sovereign, blaspheme the Church, or stir audiences to political radicalism. An 1843 act expanded the division’s powers, calling upon it to dam any play that threatened not simply the “Public Peace” however “Decorum” and “good Manners.”

Hardly chosen for his or her inventive sensibilities or information of theatrical historical past, the boys employed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Workplace have been principally retired navy officers from the upper-middle class. From the Victorian period on, they scrutinized performs for references to racial equality and sexuality—notably homosexuality—vulgar language, and “offensive personalities,” as one guideline put it.

Twentieth-century English theater was, because of all this vigilance, “topic to extra censorship than within the reigns of Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I,” wrote the playwright and former theater critic Nicholas de Jongh in his 2000 survey of censorship, Politics, Prudery and Perversions. The censors suppressed or bowdlerized numerous works of genius. As I thumbed by each play I may consider from the 1820s to the Nineteen Sixties (earlier manuscripts, bought as a part of an examiner’s non-public archive, might be seen within the Huntington Library in California), it grew to become clear that the censors solely received stricter—and extra prudish—over time.

“Don’t come to me with Ibsen,” warned the examiner E. F. Smyth Pigott, properly demonstrating the censors’ recurring tone. He had “studied Ibsen’s performs fairly rigorously,” and decided that the characters have been, to a person, “morally deranged.”

In cardboard packing containers stacked on infinite rows of steel shelving, string-tie binders maintain the unique variations of hundreds of performs. The textual content of every is accompanied by a typewritten “Readers’ Report,” most of them a number of pages lengthy, summarizing the plot and cataloging the work’s flaws in addition to any redeeming qualities. That’s adopted, when obtainable, by typed and handwritten correspondence between the censors and the candidates (normally the play’s hopeful and ingratiating producers).

These studies can at occasions be as entertaining because the performs themselves. On Beckett’s Ready for Godot, one examiner wrote: “Omit the enterprise and speeches about flybuttons”; on Sartre’s Huis Clos: “The play illustrates very nicely the distinction between the French and English tastes. I don’t suppose that anybody would bat an eyelid over in Paris, however right here we bar Lesbians on the stage”; on Camus’ Caligula: “That is the kind of play for which I’ve no liking in any respect”; on Tennessee Williams: “Neuroses grin by all the things he writes”; and on Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin within the Solar: “ play about negroes in a Chicago slum, written with dignity, energy and full freedom from whimsy. The title is taken from a nugatory piece of occasional verse about goals deferred drying up like a raisin within the solar—or festering and exploding.”

These bureaucrats have been keen, as considered one of them wrote, to “lop off just a few excrescent boughs” to save lots of the tree. They have been anti-Semitic (one profitable compromise concerned changing a script’s use of “Fuck the Pope” with “The Pope’s a Jew”) and virulently homophobic. In response to Williams’s Abruptly Final Summer time, in 1958, one Lieutenant Colonel Vincent Troubridge famous: “There was an important fuss in New York in regards to the references to cannibalism on the finish of this play, however the Lord Chamberlain will discover extra objectionable the indications that the lifeless man was a gay.”

However the censors may additionally, often, aspire to the extent of pointed and biting literary criticism. “This can be a piece of incoherence within the method of Samuel Beckett,” the report for a 1960 manufacturing of Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker begins, “although it has not that writer’s vein of nihilistic pessimism, and every particular person sentence is understandable if irrelevant.” One will get the impression that, just like the characters from a Bolaño novel, no less than a few of these males have been themselves failed artists and intellectuals, drawn to such authoritarian work from a spot of bruised and envious ego.

Certainly, one examiner, Geoffrey Dearmer, thought of among the many extra versatile, had written poetry in the course of the Nice Battle. He reported to the Lord Chamberlain alongside the tyrannical Charles Heriot, who had studied theater at college and labored on a manufacturing of Macbeth earlier than transferring, nonetheless as a younger man, into promoting, journalism, and e-book publishing. He was identified, de Jongh wrote, for being “gratuitously abusive.” (Heriot on Edward Bond’s 1965 Saved: “A revolting beginner play … a couple of bunch of brainless, ape-like yobs,” together with a “brainless slut of twenty-three dwelling together with her sluttish dad and mom.”) One other examiner, George Alexander Redford, was a financial institution supervisor chosen primarily as a result of he was buddies with the person he succeeded. When requested in regards to the standards he utilized in his resolution making, Redford answered, “I’ve no vital view on performs.” He was “merely bringing to bear an official standpoint and maintaining a regular. … There aren’t any ideas that may be outlined. I comply with precedent.”

Chris Hoare for The Atlantic

An examiner’s notes on Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Sizzling Tin Roof

The director Peter Corridor, writing in The Guardian in 2002 about his experiences with the censors, mentioned that the workplace “was largely staffed by retired naval officers with terribly filthy minds. They have been so alert to filth that they usually discovered it when none was meant.” As soon as, he known as to ask why some traces had been minimize from a play he was directing:

“Everyone knows what’s happening right here, Corridor, don’t we?” mentioned the retired naval officer angrily. “It’s up periscopes.” “Up periscopes?” I queried. “Buggery, Corridor, buggery!” Truly, it wasn’t.

As comedian as these males appear now, they wielded huge, unexamined energy. The correspondence filed alongside the manuscripts reveals the extent to which the pressures of censorship warped manuscripts lengthy earlier than they even arrived on the censors’ desks. Managers and manufacturing firms checked scripts and steered adjustments in anticipation of scrutiny. In a 1967 letter, a consultant of a dramatic society desirous to stage Ready for Godot writes, “On web page 81 Estragon says ‘Who farted?’ The director and myself are involved as as to whether, throughout a public presentation, this may offend the legal guidelines of censorship. Awaiting your recommendation.” Presumably, the reply was affirmative.

Chris Hoare for The Atlantic

An examiner’s report on Samuel Beckett’s Ready for Godot

Playwrights additionally carried out their very own “pre-pre-censorship”—limiting the scope of their material earlier than and in the course of the writing course of. In keeping with the 2004 e-book The Lord Chamberlain Regrets … A Historical past of British Theatre Censorship, way back to 1866, the comptroller of the LCO, Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, “explicitly recommended examiners for working this ‘oblique system of censorship’ as a result of it enabled the Workplace to maintain the variety of prohibited performs to a minimal and forestall considerations about repression.”

Some performs made it previous the censors solely because of human error. Once I met Kate Dossett, a professor on the College of Leeds who focuses on Black-theater historical past, she informed me that the case of the playwright Una Marson is an instance of what “will get hidden on this assortment.” Marson’s 1932 play, At What a Worth, depicts a younger Black girl from the Jamaican countryside who strikes to Kingston and takes a job as a stenographer. Her white employer seduces—or, in right now’s understanding, sexually harasses—and impregnates her. The drama is a delicate exploration of miscegenation, one of many core taboos that the LCO usually clamped down on. However the play was accredited as a result of the examiner—confused by the protagonist’s class markers and schooling—didn’t understand that she was Black.

Chris Hoare for The Atlantic

The script of Una Marson’s At What a Worth

“This play is to be produced by the League of Colored Peoples however it appears to don’t have any specific relation to the objects of that establishment besides that the scene is in Jamaica and a number of the minor characters are colored and communicate a kind of diverting dialect,” the report states. “The primary story is presumably about English folks and is an old school artless affair.”

From the start, some outstanding figures fought in opposition to the system of censorship. Henry Brooke’s Gustavus Vasa bears the excellence of getting been the primary British play banned below the Licensing Act of 1737. The work, ostensibly in regards to the Swedish liberator Gustav I, was interpreted as a thinly veiled assault on Prime Minister Robert Walpole. Responding to the ban in a satirical protection of the censors, Samuel Johnson wrote that the federal government ought to go additional, and make it a “felony to show to learn with out a license from the lord chamberlain.” Solely then would residents be capable of relaxation, in “ignorance and peace,” and the federal government be secure from “the insults of the poets.”

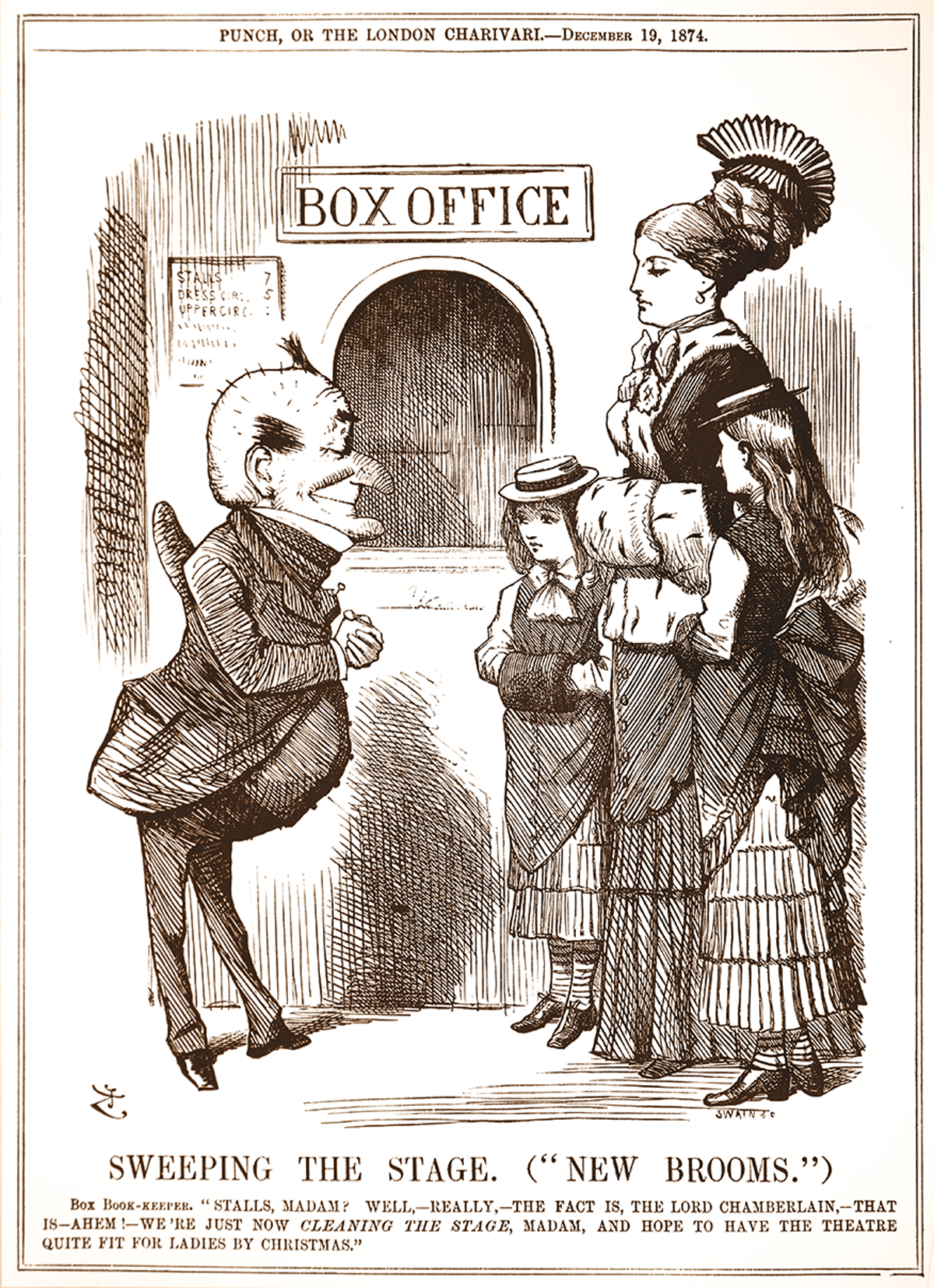

Common Historical past Archive / Getty

A cartoon from 1874 satirized the Lord Chamberlain’s makes an attempt to scrub up the stage.

Henry James, in his day, spoke out in protection of the English playwright, who “has much less dignity—because of the censor’s arbitrary rights upon his work—than that of another man of letters in Europe.” So, too, did George Bernard Shaw. “It’s a frightful factor to see the best thinkers, poets and authors of recent Europe, males like Ibsen,” Shaw wrote, “delivered helplessly into the vulgar fingers of such a noodle as this despised and incapable outdated official.”

By the point the Theatres Act of 1968 abolished the censorship of performs, social attitudes have been altering. The inflow of staff from Jamaica and different nations within the Commonwealth within the Nineteen Fifties challenged the steadiness of racial dynamics; intercourse between males was decriminalized in England and Wales in 1967; divorce grew to become extra widespread; and the rock-and-roll period destigmatized medication. For years, theaters had been making the most of a loophole: As a result of the LCO’s jurisdiction utilized solely to public performances, theaters may cost patrons a nominal membership charge, thereby reworking themselves into non-public subscription golf equipment out of the censors’ attain.

It should have gotten lonely, making an attempt to face so lengthy in opposition to the altering occasions. “I don’t perceive this,” Heriot wrote, plaintively, about Hair. The American musical was banned thrice for extolling “grime, anti-establishment views, homosexuality and free love,” however in the long run, one will get the impression that the censors simply gave up. Alexander Lock, a curator on the library, pointed me to Heriot’s report on the ultimate model of the musical. The ache of defeat in his voice is sort of palpable: “A curiously half-hearted try and vet the script” had been made, he wrote, however many offenses have been left intact.

Hair opened on the Shaftesbury Theatre in September 1968. That month, by royal assent, no new performs required approval from the Lord Chamberlain’s Workplace, which was left to commit its consideration to the planning of royal weddings, funerals, and backyard events.

Some could also be tempted to dismiss the censors’ legacy as restricted to, as a 1967 article in The Instances of London had it, “the trivia of indecency.” However the harm was far deeper. The censors, de Jongh wrote, stunted English theater, saved it frivolous and parochial, and prevented it from coping with “the best points and anguishes of this violent century.” No playwrights addressed “the fascist regimes of the Nineteen Thirties, the method that led to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the ghastliness perpetrated by Hitler and Stalin, or the tyrannies skilled in China and below different totalitarian leaderships. No surprise. Their performs would have been disallowed. Within the Nineteen Thirties you could possibly not win licences for performs which may offend Hitler or Mussolini or Stalin.” Shakespeare by no means “needed to put up with” censorship so “rigorous and narrow-minded,” Peter Corridor wrote. His “richest performs and his most interesting traces, full of erotic double meanings, would have been well excised by the Lord Chamberlain’s watchdogs.”

These practices could strike us right now as outlandish and anachronistic. Many people take without any consideration inventive license and the liberty of expression that undergirds it. However the basis upon which these rights—as we consider them—are located is way much less immutable than we want to think about. As current traits in the US and elsewhere have proven, advances towards better tolerance are reversible.

Certainly, many People on each the fitting and the left accurately sense this, even when they don’t all the time perceive what real censorship appears to be like like. Activists on school campuses have confused the power to occupy and disrupt bodily house for the fitting to dissent verbally. In the meantime, Elon Musk warns that “wokeness” will stifle free speech whilst he makes use of the social-media web site he owns to govern public debate.

Perusing the performs within the Lord Chamberlain’s archive is, amongst different issues, a reminder of what censorship actually is: authorities energy utilized to speech to both restrict or compel it. And it’s also a reminder that in the long run, many such makes an attempt backfire. They reveal, as Sir Roly Keating, who was chief govt of the library from 2012 till the start of this 12 months, informed me, extra in regards to the censors’ personal “fears, paranoias, obsessions” than they ever reach concealing.

Chris Hoare for The Atlantic

Contained in the archive

There may be additionally the sheer truth of what Keating known as “this extraordinary imposition of paperwork.” Simply because the Stasi archive gives unparalleled perception into the interaction of artwork and politics in postwar East German society, and the Hoover-era FBI’s copious information on Martin Luther King Jr., James Baldwin, and different Black American luminaries quantity to a invaluable cultural repository, the Lord Chamberlain’s archive can now be seen as one of many preeminent collections of Black and queer theater within the English-speaking world. It contains not simply the performs that have been staged, but additionally those who have been rejected, and in some circumstances a number of drafts of them. These are exactly the sorts of works that, with out the backing of establishments which have the assets to guard their very own archive, might need been misplaced to historical past.

“Theater’s an ephemeral medium,” Keating informed me. “Early drafts of performs change on a regular basis; many don’t get revealed in any respect.” Among the many many ramifications of censorship, I had not adequately thought of this one: the diploma to which methodical suppression can create essentially the most meticulous assortment. It’s a deeply satisfying justice—even a type of revenge—that the hapless bureaucrats who endeavored so relentlessly to squelch and block unbiased thought have as an alternative so painstakingly preserved it for future generations.

Assist for this text was offered by the British Library’s Eccles Institute for the Americas & Oceania Phil Davies Fellowship. It seems within the March 2025 print version with the headline “All of the King’s Censors.” If you purchase a e-book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.